Share

The Centre spoke with Christina Wille, co-founder and managing director of Insecurity Insight. For over 10 years, Insecurity Insight has been working with aid agencies, policy makers and researchers to find new ways of documenting violence and its impact. We discussed their innovative ways to collect data, how they use Natural Language Processing algorithms and the Humanitarian Exchange Language, and the importance of connecting data to policy making.

This interview was conducted by Becky Band Jain, the Centre’s Communications Manager. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell us about Insecurity Insight.

Insecurity Insight investigates threats facing people living and working in dangerous contexts. We are known for our innovative data collection and analysis methods that provide insights to aid workers and agencies and those concerned with the protection of health workers, educators, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees. Our aim is to empower those who deliver vital services and to give a voice to those affected by insecurity.

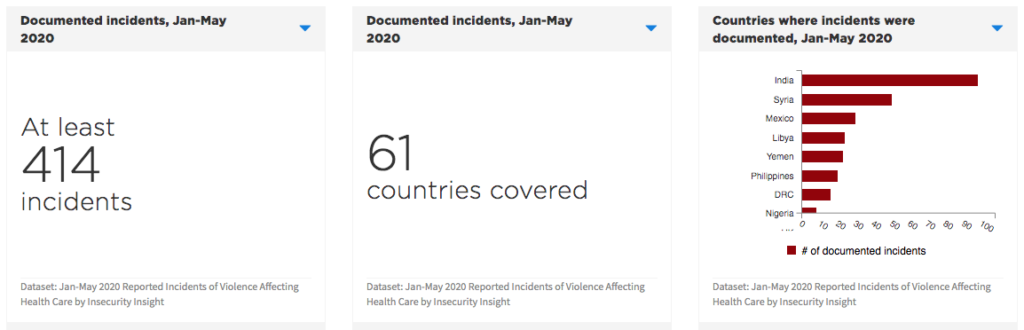

We support organisations by monitoring and analyzing media sources with a focus on five areas: violence or the threat of violence affecting the delivery of aid; attacks on healthcare; attacks on education; violence in IDP and refugee settings; and sexual violence against aid workers. Every year, we compile the data on attacks on health care for the annual Safeguarding Health in Conflict report which is produced by a group of NGOs working to protect health workers and launching tomorrow (register here for the event). We provide monthly news briefs and produce country-focused threat and risk assessments. We also provide a reporting mechanism for survivors of sexual violence.

What is innovative about your data collection and analysis methods?

We look at individual incidents and encode aspects around them according to the six Ws: ‘who did what, to whom, where, when, and with what weapons’. We’re developing an algorithm using NLP methods to classify open source information relevant to the areas we are monitoring. The algorithm can scan thousands of news stories and identify those that seem most relevant to what we’re looking for. It’s been trained on hundreds of events that we found manually, and we regularly retrain the algorithm on new events.

For example, the term ‘Ebola’ was not in our algorithm but we realized there are a lot of attacks on healthcare workers related to an Ebola response, most recently in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. We needed to make sure that the new keywords that occurred within the latest events were fed into the algorithm, and retrain it to remain up-to-date for the terms we are looking for. The COVID-19 pandemic also required that we expanded search terms to include works like ‘quarantine’ or ‘contact tracing’. So we are combining a lot of manual search and understanding of the issue with retraining the algorithm.

We have also developed a ‘smart panel’ to automatically geocode text-based information. By putting text, for example from a news article, into the smart panel, the system automatically identifies the 6Ws. We are getting this text-based information from a variety of online sources, and getting them geocoded is a considerable task. We can take anything from the Internet—social media, local news, international news. For the moment, we have about 450,000 sources going through the newsreader per month.

How are you using the Humanitarian Data Exchange?

One of the reasons we love HDX is that it allows us to select specific datasets and share them with different user groups. For instance, we started sharing the events around aid security and the COVID-19 response on HDX. The HDX platform was a natural choice to get this data out quickly and ensure that it can be used in conjunction with other COVID related data, such as infection rates or school closures. We also share data on attacks on education or the kidnapping, killing or arrests of aid workers.

Insecurity Insight’s core audience is security risk managers in aid agencies who take daily strategic decisions on where they could or should not be in particular circumstances. Through HDX, we have been able to expand our reach.

We started using the Humanitarian Exchange Language format in 2017. The concept is good, and there’s more we can do with it. We include Quick Charts in our Excel sheets and also embed them on our website. We find them useful because we can create many different versions of the charts.

We are also currently working with the team to see how we can include our data in the Data Grids. We really appreciate this new feature. It’s so user friendly to give people access to data by country. We are keen to get our data into the Grids. The State of Open Humanitarian Data Report was also a useful exercise—it’s important to take stock.

What are some of the challenges you face when working with humanitarian data?

Data on its own isn’t useful. It requires a full cycle of extracting and processing, and going through the policy process. This is all challenging: getting access to the right data, working on it, feeding it back to the people who need it to make decisions. The policy process is especially challenging: What does the data mean for the actions people need to take? For example, we presented an analysis on Ebola violence to policymakers but it wasn’t immediately clear what they needed to do next. It took us weeks of working together to come up with recommendations which led to the development of a mobile guide on how to deliver emergency health care in insecure settings. This was developed with help from the Cornerstone OnDemand Foundation.

“We need to do much more with data literacy to get more meaning out of the data and to understand what needs to be done with it. ”

Part of our audience has high data literacy levels, part has low data literacy levels, and some are frightened by or even have an allergy to data. We are trying to improve data literacy for everyone and to make accessible products. For example, we developed the Security Incident Information Management (SIIM) concept for aid agencies and we have manuals to help partners incorporate data collection and use of their own security incidents into their risk management practices.

What are some of the trends you are seeing with your work?

There’s a move towards more incident-level data and more transparency about data. A very interesting example of this is the WHO Surveillance System for Attacks on Health Care. You can see quite a lot of detail about each event, and that’s really new and quite revolutionary but it needs further improvements.

People are sharing more of their data, which is a trend that HDX is supporting enormously. This is really important because we need to cross check the data and understand more about it. Otherwise it just remains a figure and you can’t do much with it. Unfortunately many policy reports still do not publish or give access to incident level data. I am not sure why this continues to be an acceptable practice. I wonder whether people are concerned with others finding mistakes in the data and that this can turn into a political problem. People can get punished instead of applauded for what they are doing.

There are obviously legitimate concerns about not making data available that puts individuals or operations at risks. There are usually ways around it that allow access to the data without exposing individuals. The HDX team can help by emphasizing the importance of sharing what you have even if it’s not perfect. As a community, we can all work on this together.

What’s next for Insecurity Insight?

We are going to improve our algorithms and share more data with more people. We need to find more channels of sharing data effectively, and provide data in a way that people can use it for policy making. The data should feed into decision making. We need to chop the data into chunks and provide messages on what it means. Also please follow our bulletins covering COVID-19 aid security and data on HDX.

What do you love about what you do?

What I love most is working with people who try to do new things and who are not bogged down by existing structures. It’s extremely rewarding. I especially enjoy interacting with people at the Centre and others in this sector who are innovating.