Share

As the Centre for Humanitarian Data enters its third year of operations, we have been reflecting on our work and our role. In the coming months, we will be developing a next phase plan for the Centre to take us beyond our initial start-up period into a steady state with a focus on four areas: data services, data responsibility, data literacy and predictive analytics.

Last spring I became aware of the work of Jim Collins, author of Good to Great and Turning the Flywheel. He was interviewed by Kara Swisher on her Recode Decode podcast which I have found particularly helpful in understanding the big societal issues around data and technology. In their conversation, Collins explained why some companies become great and others do not. The answer lies in the flywheel principle.

Collins uses the idea of a flywheel, a rotational device that stores energy, as a business analogy for understanding the causal links in an operation that create compounded momentum to drive more value for more people. Collins provides an example from his work with Jeff Bezos in 2001, just after the dot-com bubble had burst. As he describes it, the Amazon flywheel started with lower prices on more things which led to more customers which led to more third-party sellers. This led to more efficiency in their processes and optimizing fixed costs (fulfillment centers and servers), and this allowed them to lower prices further, starting the loop again.

This flywheel is still the basis of Amazon’s business model even as it has been renewed and extended many times (think AWS, Prime Video, and Whole Foods), making it one of the wealthiest and most influential companies in the world.

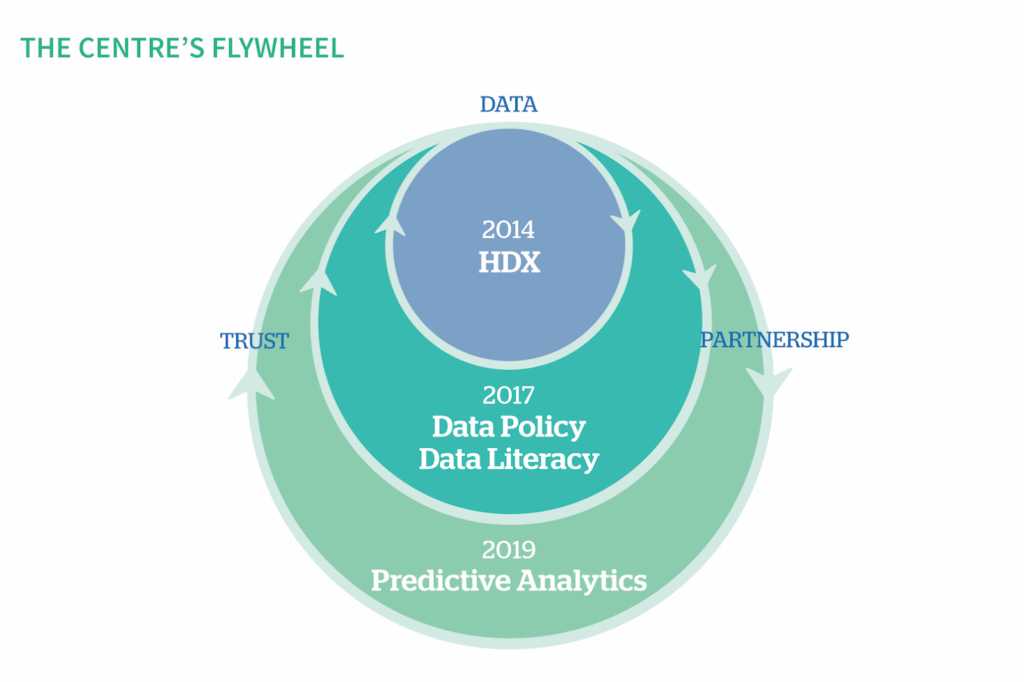

The Centre’s Flywheel: Data, partnerships, trust

I was drawn to the logic of the flywheel effect and spent time over the summer with our Business Strategy Fellow to understand what drives the Centre’s momentum. Although we are not seeking to make a profit, we do want to create more value for our community year-on-year and ultimately increase the use and impact of data in the humanitarian sector.

The starting point for the Centre’s flywheel is data. People come to us for data: to find it, to share it, and to add value to it. This started with the launch of the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) in 2014 which preceded the Centre but involved the same core team.

The 2014 West Africa Ebola Outbreak was our first opportunity to make the case for a system-wide data aggregation platform. We did two things that created early momentum: we made it easier for people to find Ebola-related datasets from many sources (speed) and we added value to the data through visualizations (insight).

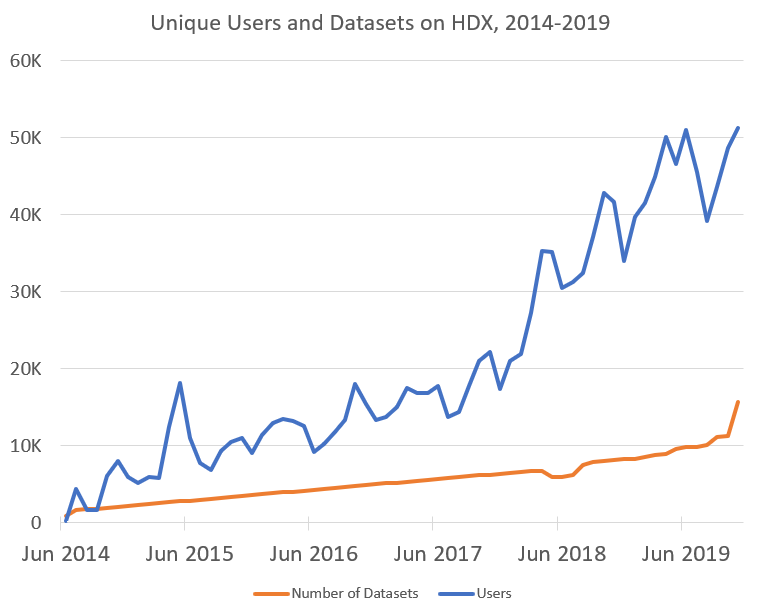

This promise of ‘speed to insight’ brought both data consumers and data providers to the site which resulted in partnerships that expanded the reach and relevance of HDX beyond this initial use case. For instance, WFP was the first big UN agency to join HDX by sharing their food prices data. In return, we created a custom data visualization for them (which is still being maintained) and tracked dataset downloads which showed that more people were accessing their data through HDX than through their own site. WFP referred to this as the ‘HDX advantage’: if your organization’s goal is for more people to use your data, then share it with HDX.

Our expertise in working with data and building enduring partnerships created trust. And this trust led to more data being shared by more partners for more users, driving the next turn of the flywheel. More demand (and more investment) allowed us to optimize the platform, from improving search to using HXL-tags to automatically generate embeddable charts.

We extended this flywheel in 2017 when we launched the Centre. We continued to manage HDX and added new workstreams for data responsibility and data literacy. Our progress with introducing guidance on data responsibility and offering data skills training is directly related to our competence with data, the strength of our partnerships, and the trust we have created. We further extended our flywheel in late 2019 with the addition of a workstream on predictive analytics that is focused on modelling and peer review. At this stage, I don’t foresee more extensions beyond these four workstreams.

In parallel, our audience or ‘customer base’ has expanded from the technical data manager who uses HDX to the less-technical humanitarian affairs officers and heads of office who need to assess data quality or the outputs of a predictive model before making a decision. And so our flywheel keeps turning, reaching more people based on data, partnerships and trust.

It perhaps goes without saying that key enablers for our work include OCHA’s coordination mandate, donor funding, and a great team. Limitations include our size: we are a small entity within a larger office (OCHA), organization (the UN), and system (humanitarian). We represent about 1% of OCHA’s annual budget. But given the big goal is to reach a higher percentage of people in need of assistance every year within a $28 billion requirement, our hope is that we can play an outsized role in helping to achieve this.

Plans for 2020

As we plan for our next phase, we are considering how to accelerate momentum while also meeting near-term deliverables. Our priorities for 2020 include the following:

- We want to increase the completeness of the HDX data grids which highlight what data is available and missing for priority humanitarian crises. The grids are currently about 50% complete across 14 locations.

- We are creating an algorithm within the HDX infrastructure that will identify sensitive data before it is exposed publicly. We will work to de-risk this data through a streamlined statistical disclosure control process.

- We will work with Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) partners to develop joint operational guidance on data responsibility and will support OCHA offices with uptake of the OCHA Data Responsibility Guidelines.

- We will expand our Data Literacy Foundation Programme to more OCHA staff in more locations and offer training opportunities to our partners.

- We will roll out our Peer Review Framework for Predictive Analytics in Humanitarian Response and support all OCHA offices with projections in their Humanitarian Response Plans.

Keeping Our Eye on the Ball: Data

One piece of advice from reading and listening to Collins that has stayed with me is to remember that the flywheel is not a circle with points but a causal loop. It is critical to get the sequence right: each component depends on the other components, especially the primary component, in our case data and HDX.

As we grow and respond to new requests, it is critical that we continue to invest in the core drivers of our success even if those aspects fade from the so-called hype cycle. This means ensuring that HDX remains well resourced and responsive to the demands of our partners, even as donor interest in funding platforms and tools for data sharing has diminished in recent years. Predictive analytics is an exciting area with the potential to transform how response happens but models can only work based on good data used by skilled staff in an ethical way.

According to Collins, a good flywheel can last ten years, and in some cases, decades. Of course nothing lasts forever, not even dominant companies like Amazon. But I hope that the Centre will continue to create value with data through trusted partnerships in the years to come. We welcome feedback to ensure we are on the right track.

To learn more about the flywheel concept, read Jim Collins’ books and articles and listen to him being interviewed by Kara Swisher in this podcast.